Homes that

Updates from the Women Against Homelessness and Abuse (WAHA) initiative

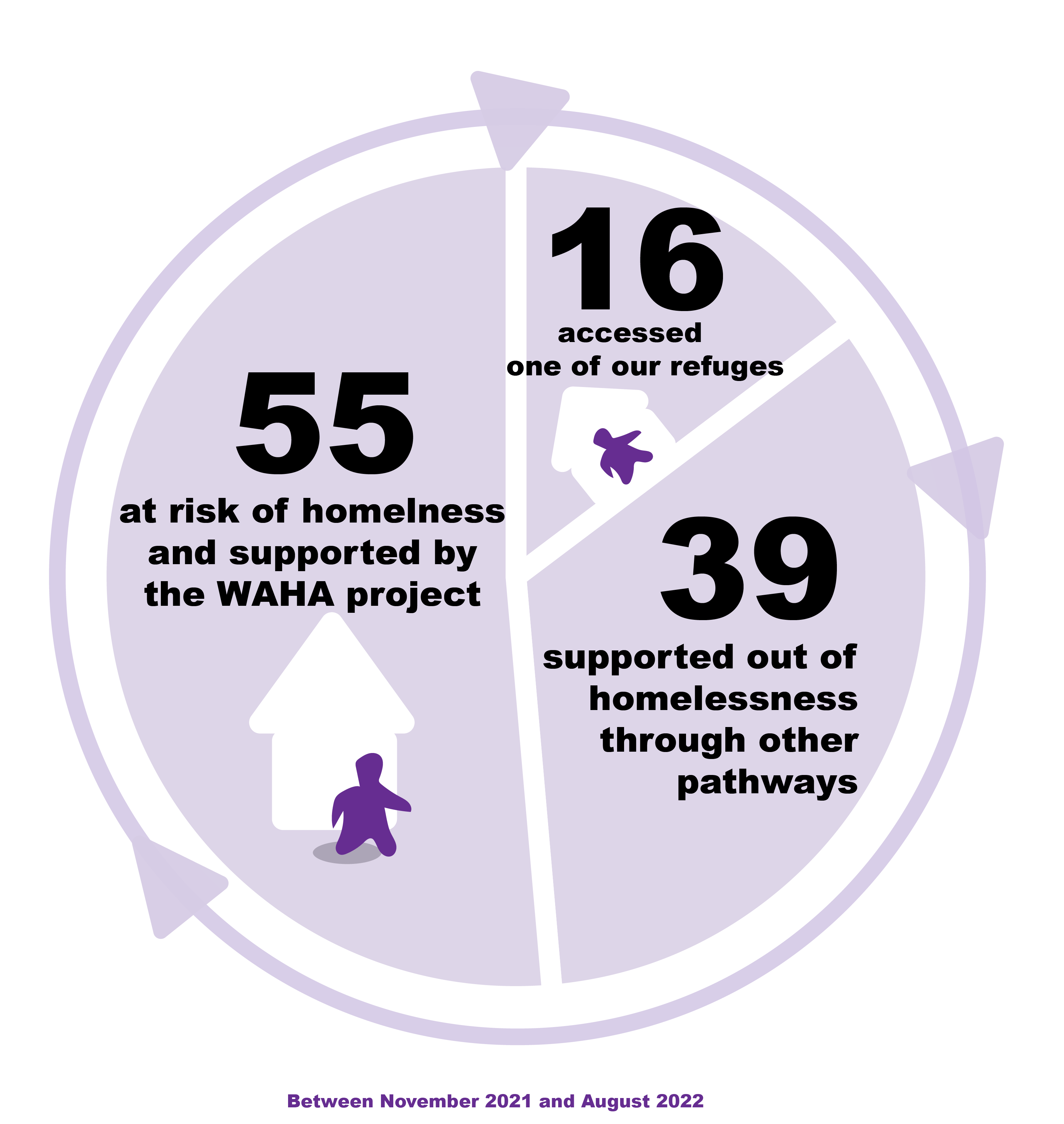

For 34 years our refuges have been a sanctuary where women surviving abuse have been inspired to heal and move on from the trauma of gender based violence. Since 2018 our Women against Homelessness and Abuse (WAHA) initiative has been a springboard for collaboration within the specialist by and for sector, providing a pioneer, one of a kind, specialist and intersectional housing advice service for black and minoritised survivors of gender based violence

ABOUT

What is WAHA

Women against Homelessness and Abuse (WAHA) is an initiative for Black and Minority Ethnic women jointly run by the Latin American Women’s Aid in partnership with the OYA consortium of BME refuges in London.

WAHA aims to address Black and monitory ethnic women’s intersecting pressures of poverty, homelessness and gender violence through promoting changes in housing policy and practice in the UK using a rights-based approach. It is a policy but also a frontline project advising, representing and supporting survivors to make appeals and secure safe and appropriate accommodation, in an environment free from violence and intimidation.

Our ultimate goal is to work with policy makers and practitioners to affect change to ensure the housing needs of BME survivors are met. We envisage a world where no woman will be forced to endure abuse for fear of becoming homeless, where women fleeing violence are able to access their rights to safe accommodation without that process furthering the cycle of abuse.

A key outcome of the project has been consolidating influencing capacity amongst partners, improving the knowledge base on housing options for BME women and building tools for strategy development and sustainability in the by and for sector.

RESEARCH

A Roof, not a Home

Published in October 2019, this report addresses the housing experiences of Black and minoritised women survivors of gender violence. It draws on the first year of the Women Against Homelessness and Abuse (WAHA) project funded by Trust for London and jointly run by the Latin American Women’s Aid (LAWA) and the London Black Women’s Project (LBWP) under the OYA consortium of by and for specialist Black and minoritised ending VAWG organisations. Combined LAWA and LBWP have a longstanding history of 60-plus years working with Black and Minoritised women and running refuges and advice centres for women affected by different forms of gender-based violence.

The WAHA project is aimed at addressing Black and minoritised women’s intersecting pressures of poverty, homelessness, and gender violence, through promoting changes in housing policy and practice in the UK using a rights-based approach. Hence, it is policy-focused, but it is also a frontline project advising women and acting on their behalf to help them access and achieve safe and appropriate accommodation. The project also endeavours to build the capacity of professionals with the goal of ensuring all homeless women are treated fairly and with dignity. WAHA’s ultimate goal is to work with policy-makers and practitioners to effect change in the way the housing needs of vulnerable women are met. We envisage a world where no woman will be forced to endure abuse for fear of becoming homeless, and where minoritised women fleeing violence are able to access their rights to safe and suitable accommodation without that process furthering the cycle of abuse.

Methodology

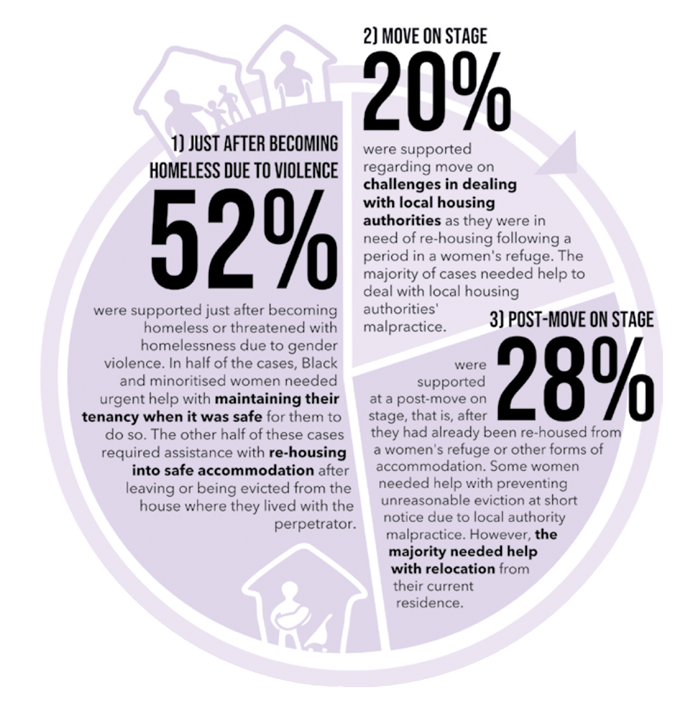

The findings presented in this report builds on WAHA case work analysis and consultations with refuge workers and residents. We carried out an in-depth analysis of 69 housing cases of Black and minoritised survivors supported between July 2018 and July 2019 by the WAHA housing legal advisor. Detailed information about service users and their cases were used for this report from LAWA’s and LBWP’s centralised database system. The cases were then analysed and clustered based on three different stages where housing advice and support was sought, and particular challenges faced by the service user.

The WAHA consultations occurred between November 2018 and March 2019 with Black and minoritised refuge residents and refuge workers from LAWA, LBWP and Asha, covering a total of five boroughs 2: Lewisham, Barnet, Newham, Haringey and Islington. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with 7 refuge workers, where they were asked to discuss the main housing issues experienced by Black and minoritised survivors and the main challenges they are presented with whilst supporting them. A total of 5 focus groups were held with 38 Black and minoritised residents where they were asked about the intersecting housing challenges they have faced in their journeys of fleeing violence. This covered different stages, from leaving their abusers, experiences living and moving on from Black and minoritised refuges and other forms of accommodation, to their experiences dealing with housing authorities and other statutory services. The workshop finished with an arts-based activity where women were asked to either individually or collectively represent their housing aspirations through drawing and collage. A note-taker was present during all these activities to ensure these were thoroughly documented without a need for recording. A thematic analysis was carried out from the interviews and focus groups to identify the main issues experienced by Black and minoritised women regarding housing.

All women who have participated in this research provided consent for their personal data and information to be stored and processed for the purpose of this project. In order to preserve anonymity and confidentiality, names and personal details of participants have been changed and/or omitted whenever this could lead to their identification. Names of local authorities and organisations were also omitted and removed from statements, as a means to avoid generalisations that may potentially single-out specific organisations and local authorities. Methodologically, this is a qualitative research which is not intended to be an in-depth review of specific local authorities’ practices. Although we have come to identify a series of concerning practices, we acknowledge that local authorities have complex organisational structures and are increasingly operating under pressure.

Key Findings

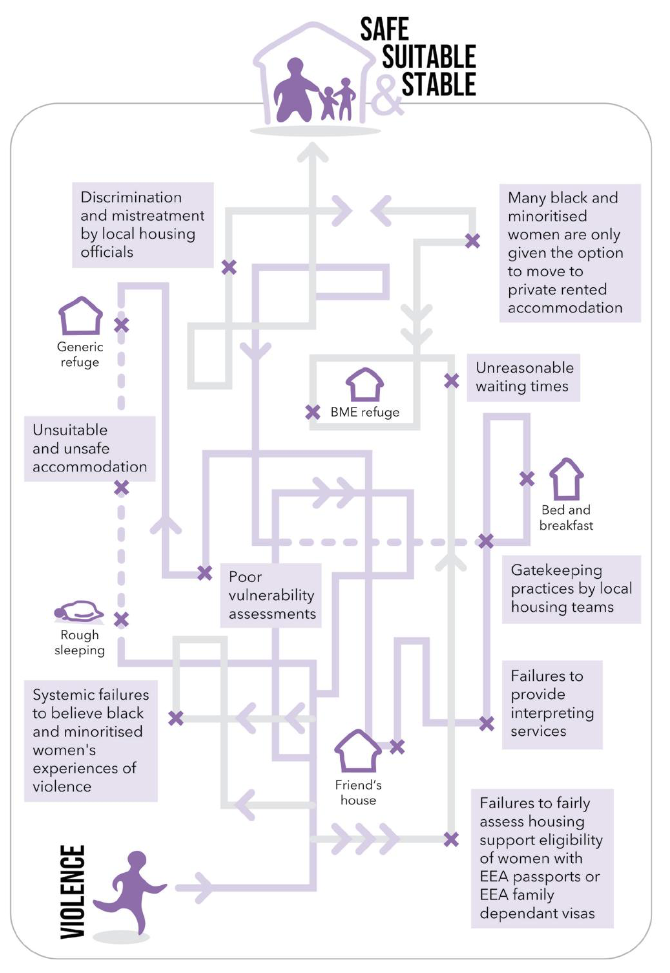

Our research reveals that Black and minoritised survivors are faced with complex structural barriers to access safe and stable forms of accommodation. They are often at high risk of homelessness and re-victimization at different stages of their journeys of fleeing violence; not only at the point of exiting a violent relationship but also for an extended period thereafter. Their journeys reveal a cycle of victimization that goes beyond the violence perpetrated by their direct abusers; their trauma is furthered by systemic and institutional failures and discrimination in the ways in which public authorities (the police and local housing authorities in particular) deal with their cases of violence.

The re-victimization experienced by Black and minoritised survivors plays out not only in terms of poor welfare/housing provisions and structural sexism but is also compounded by intersecting structures of oppressions based on race, immigration status, language barrier, class and/or disability. Our direct casework experiences through the WAHA project also shows a range of housing issues arising at the different stages of Black and minoritised survivors’ journeys, from leaving their abusers, moving on from refuges, to issues arising even after they have been re-housed.

Summary of key challenges

• Failures by the councils to provide interpreting services, accessible information & referral options

• Institutional discrimination and poor treatment of Black and minoritised homeless survivors by local housing officials based on their race, immigration status, and/or English ability.

• Entrenched gatekeeping practices by local housing teams

• Failures by housing authorities to re-house survivors in safe, suitable and stable accommodation at the point of move on from refuge accommodation.

Reflections on Impact and Challenges 5 years on

• After 5 years of work, structural conditions in this area have not improved.

• Black and minoritised women continue to face severe housing inequalities

• The specialist Black and minoritised sector currently provides 296 refuge bed spaces in the UK but demand (in 2020-21) has demonstrated that we need an additional 1,172 bed spaces (@Imkaan)

Unfortunately, temporary accommodation is often unsuitable and unsafe for women and children, further re traumatising them. This is due to a number of interlinked issues:

(1) Chronic shortage of suitable and affordable accommodation across all local authorities

(2) Precarity in their living conditions due to immigration status and cost of living crisis. Often, migrant women are either #NRPF or wrongly classified as such. Support SHOULD be given to all survivors of abuse regardless of their immigration status

(3) Women from our communities are also more likely to have precarious jobs, be more at risk of poverty and have weaker networks to rely on.

(4) Lack of effective and sensitive responses by housing officers within councils when supporting BME VAWG survivors.

THE OYA

CONSORTIUM

Founded in 2016, OYA is a membership consortium of by and for Black and minoritised ending VAWG organisations delivering frontline, capacity building and sustainability support services across London. OYA comes together in solidarity to address the structural and institutional nature of inequality, disadvantage and under-representation by addressing critical needs of Black and minoritised women, their children and young women and girls, which are systematically neglected by the state. OYA is also aware that ‘competition from within’, encouraged through tendering processes have favoured generic women’s organisations. OYA commits to a non- competition framework and promotes collaboration in terms that are fair and equal, open and transparent, participatory and inclusive.

Who we are

Why OYA? – Origins and Commitments

The name OYA has many references across cultures, communities and countries. In naming the consortium, the agreed meanings are as follows:

The OYA slogan is Equality, Innovation and Social Change.

By Equality we mean to achieve equal representation, equality of opportunity and equal rights for BME women and girls. By Innovation we mean to challenge patriarchal institutionalism and structuration by maintaining a transformative and dynamic engagement in the way we create space, represent voice and uplift BME women and girls. By Social Change we seek social justice.

Our goal is that led by and for black and minoritised VAWG ending organisations achieve self-determination through strategic initiatives supporting housing options for women survivors of VAWG in the UK.

The OYA Member organisations

LAWA has been providing the only refuges for Latin American women surviving domestic violence and other forms of VAWG in London over the past 34 years. LAWA provides services pan-London with special focus on Hackney, Islington and Barnet, and women from all across London can access our services. We also offer holistic and intersectional services, providing everything a BME woman and their children need to recover from abuse and live empowered lives. We currently operate 3 refuges with 32 bed spaces.

Provides specialist refuge accommodation for BME women from across London; our refuges are located in Newham and Haringey and we now have the opportunity to open new emergency refuge spaces.

We currently operate 4 refuges, with 29 bed spaces, in Newham. MHCLG’s emergency funding has enabled us to open 16 new spaces in Newham and one refuge in Haringey, which has 4 spaces.

LBWP also provides counselling for adult and young women, a free legal service, including support for migrant women and advocacy & advice

is a specialist led by and for BME women’s organisation, primarily for South Asian, Turkish & Middle Eastern women with over 30 years’ experience of delivering a holistic range of services. Ashiana is an organisation working within feminist principles. We acknowledge that many women at risk of VAWG will want to seek support from ‘women’ only services where they will also have access to ‘women’ only space.

We deliver specialist refuge, advice and counselling services for BME women and girls who have experienced or are at risk of VAWG, including harmful practices. We deliver a specialist legal service for women with insecure immigration status. We are based in Waltham Forest operating refuges with a total of 21 bedspaces. 2 refuges are specifically for women affected by harmful practices.

is a dedicated specialist Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) women’s organisation run for and managed by local South Asian women. We play a crucial role and provide much needed support based on an understanding of sociocultural norms, values and issues relating to forms of violence against women and girls that are specific to South Asian communities.

Asha operates from four sites – a resource centre and three refuges (safe accommodation) consisting of 19 bed spaces. We are based in the London Borough of Lambeth and predominantly receive referrals for the refuge from London. Last year we supported 412 women of which 50 stayed at our refuges.

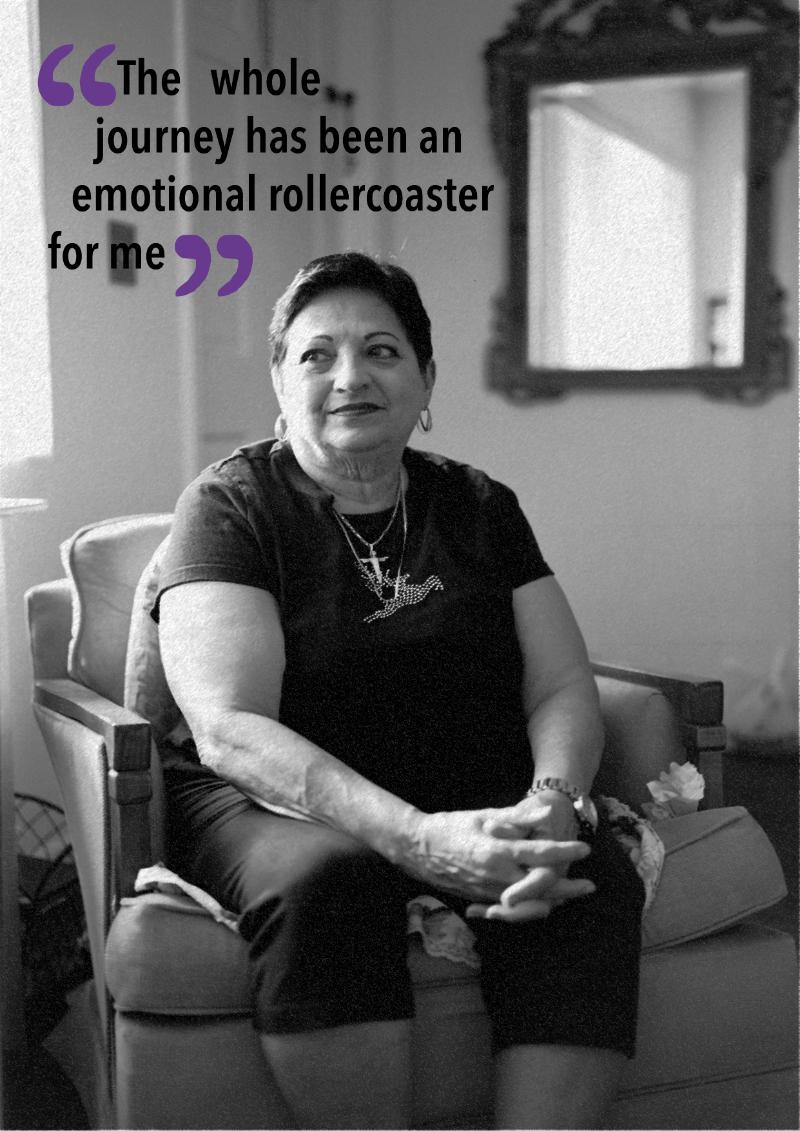

Survivor´s Voices

Angela´s story

Angela arrived at one of the LAWA refuges via an external referral. She is a 42-year-old Peruvian woman who worked as an accountant and photographer in Peru. She moved to the UK 13 years ago and was living with the perpetrator, his two children and his elderly mother until fleeing last year.

The perpetrator was verbally and sexually abusive towards Angela, controlling her life, her decisions and her finances, as well as her food intake. He was constantly threatening to “cancel” her visa, jeopardizing her right to stay in the UK. He had many affairs with other women, whilst constantly accusing Angela of infidelity. On multiple occasions when Angela tried to call the police for help, the perpetrator would threaten her by saying he would tell the police she was mentally unwell, and that his daughters and mother would testify to this.

Angela was responsible for looking after the perpetrator’s family while he was away on long business trips, making sure his children were fed and safe whilst also caring for his elderly mother.

The perpetrator made constant threats on Angela’s life and she truly believed he did not want her to leave that house alive. One of the scariest things for Angela was that the perpetrator legally possessed firearms, which were kept in the house. Angela did not feel comfortable returning to her home country, Peru, as she feared that the perpetrator would use his contacts and influence in this region to continue to harm her.

Last year, after a particularly violent incident in which the police were involved, Angela got in touch with a domestic violence organisation and left the house. The perpetrator was put on bail, facing charges for common assault. However, the coercive control charge he initially faced, was dropped.

After being referred to our services, Angela was moved to one of LAWA’s refuges for her safety, we supported her with her PTSD and anxiety. Since she moved to the refuge, Angela started to sleep better, but occasionally had nightmares where the perpetrator was trying to kill her.

In January of this year, Angela’s location in the refuge became known to the perpetrator. It is believed that the perpetrator hired a private investigator to locate Angela in order to serve her with divorce papers. This not only jeopardized Angela’s safety, but that of the other refuge residents, as well as LAWA staff. As a result of this breach, LAWA chose to move Angela into another one of our refuges in order to ensure her safety.

Angela is facing divorce proceedings and her case is in court. With LAWA’s support and help, she has been able to access counselling to process the severe emotional and physical impacts of the abuse. The WAHA project has also given her help to secure Universal Credit, housing benefits, career advice and supported her in the process to access UK citizenship (pending citizenship ceremony).

Angela is now ready to move on from the LAWA refuge into an independent living arrangement. She will be moving in with some friends as a lodger and will continue to be supported through our resettlement programme to accompany her journey to self-sufficiency (once she has the means to do so).

The way in which this case reached a conclusion is not necessarily the norm. Often, as a result of the isolation that their abusers perpetuate, survivors loose access to their support networks. What is more frequent is that survivors would only be rehoused in ‘temporary’ accommodation, or would have to access housing through the private rented sector, given that, unfortunately, securing social housing is increasingly challenging due to the massive shortage of safe and suitable accommodation for vulnerable people in the country, a situation that is most acute in the London area.

Angela’s case highlights the multitude of complexities that can arise when dealing with cases of domestic violence and coercive control. The fact that charges of coercive control have been dropped against the perpetrator highlight the difficulty faced in progressing cases of this nature, in spite of the clear psychological and emotional damage this causes survivors.

Emma´s story

Emma is a Colombian woman and mother of an autistic child. She was referred to LAWA by a local authority body because she suffered sexual, physical, psychological, financial and many other forms of abuse from her partner. Although they separated, she continued to receive death threats from him and his family, which later escalated to physical assault and harassment.

She was violently attacked in several occasions, being left significantly distressed. As her safety was compromised even at her own home, Emma was living in constant fear for her life and her daughter’s.

LAWA got involved in different stages of Emma’s case, providing support in areas ranging from psychological counselling to legal advice. LAWA’s holistic support facilitated the involvement of the police for a restriction order again her ex-partner, and provided assistance with translation of official documents and communication with authority officers, as English was not her first language.

Despite the severity of the case, the multiple agencies involved to safeguard Emma and her daughter’s life, and the restriction order; housing officers questioned her for not speaking to them directly in regards to the housing application.

In addition to this, she had to go through a long process -and it took a great amount of advocacy from

LAWA- for her to be able to stay at her place (which is adequate to her children’s needs), as she was told she was not considered a tenant but an occupant.

Emma case highlights the concerning lack of knowledge from the part of some housing officials when it comes to supporting adequately survivors of domestic violence.

Worryingly, this case also illustrated the perverse consequences of insecure forms of tenure for survivors of abuse – which effectively turn into additional barriers to safety and increased vulnerability.

Alexandra´s story

Alexandra is a 58 years old woman, who fled Spain due to domestic abuse incidents suffered by her partner during the 30 years of living together. She arrived in the UK in 2019, and due to serious medical problems as well as the pandemic she lost her job. She left the family house, fearing that her ex-partner could find her by using their daughter to get information of her whereabouts. In the UK, she was staying at her sister-in-law’s place where the perpetrator could easily come and visit at any time.

Alexandras’s sister and niece threatened her with killing her if she decided to go back to Ecuador.

Alexandra stayed for 10 months at one of LAWA’s refuge, and was supported to make a housing application. Although she was granted Temporary Accommodation by the council, the property was unsuitable to live in due to a rat infestation. The neighbours had also reported having rats in their flats, which meant it was something affecting the whole building. Despite her reporting the situation to the letting agent, it took a while for them to find a proper solution forcing Alexandra to sleep at the floor of one of her friend’s homes. Overall, it took four months for her to be offered a private and secure rent.

Alexandra’s experience with social accommodation in poorly hygienic conditions is not isolated. In recent years, council housing conditions in London have been questioned and even described as “appalling”, “unliveable” and “dangerous” by many residents who complain to their landlords without significant action being taken.

According to data from the London Assembly, 15 % of London’s social properties fail to meet the Government’s Decent Homes Standards, namely: meeting the statutory minimum standards for housing; being at a reasonable state of repair; having reasonably modern facilities and services; and providing a reasonable degree of thermal comfort.

Alexandra’s case highlights a reality that, unfortunately, is shared by a large number of vulnerable people at risk of homelessness and/or that are supported by various forms of social housing: the fact that the standards of habitability and facilities of those properties is found lacking, if not severely compromised. We have seen this kind of issue having fatal consequences in the UK in a number of cases, so it is vital to raise awareness and take prompt action in support of survivors in effective ways.

Lucia´s story

Lucia is a 36-year-old Uruguayan who arrived in the UK in 2018 with her longtime partner and a daughter from a previous marriage. For almost a decade she suffered various forms of abuse, including physical, sexual, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviour. Since the beginning of the relationship, her partner dictated all aspects of her life, from how she styled her hair to her wedding gown. Lucia lived under his supervision, as he installed cameras in the house and an app in her phone to track her daily activities and conversations. He often had jealously attacks and was aggressive towards Lucia and her daughter, including in public. Once during one of these arguments, while he was driving them home, he started speeding up the car and threatened to throw the vehicle over a cliff. This violent attitude worsened when Lucia had a child and she found herself isolated from her support network. Lucia travelled to her home country to flee this relationship and to be supported by her family; however, the perpetrator alleged she had kidnapped the child.

Lucia had to return to the UK due to a legal imposition to share the child custody. Arriving in the country she called LAWA and the authorities to take the first steps towards finding safe accommodation and protecting her son. She filled a police report. However, the perpetrator continued stalking and harassing Lucia online, and she feared that this action could trigger a more violent response. Lucia’s case was classified as high risk and she had approved a non-molestation order. LAWA supported Lucia in the court hearings and to trace a housing plan. Often, women like Lucia report this experience with the authorities as humiliating and traumatic. During this process, she revealed the need to repeat her story several times, being discredited and judged for seeking government help, and questioned for not returning to her home country.

Lucia notes that she was treated differently for being Latina. She recalled needing to beg for help and having to clarify that she did not want to be in the UK in this vulnerable situation, but that she had no alternative. Domestic violence survivors recurrently highlight the need to prove to authorities the specificity of this moment in their lives, retracing their past professional trajectories to show they are hardworking and not someone who wants to abuse the system. The lack of sensitivity and specialised training by the police and statutory services to deal with victims of VAWG means that migrant women like Lucia face a discriminatory approach before being supported.

With LAWA’s help Lucia approached the local council and applied to have her visa status unlinked from her ex-partner. She was placed in a temporary accommodation where she is living with her son. She returned to work as a teacher assistant. Although she describes the neighbourhood as a little bit insecure at night, the flat is self-contained and is in excellent condition.

Recollecting her story, Lucia says that it made a difference that she was involved in the process, that she was able to call and send emails to the local authorities, but she knows that this is not a possibility for many women, due to the lack of translator’s provision. Lucia’s regrets that women must revive traumatic moments to make themselves heard. She says that she can now finally talk about what she been through, but it was brutal and traumatizing to speak about this in the past.

Karina´s story

Karina is a 31-year-old black Brazilian woman and the mother of a newborn baby. After three years living in the UK, she became pregnant, but the news was not well received by her partner. Karina reveals that she has suffered verbal, emotional, psychological abuse, and coercive control. Her partner constantly harassed her to get an abortion, which resulted in a difficult pregnancy. During one argument she had contractions and ended up in the hospital, where the midwife contacted the authorities regarding domestic violence. That day Karina did not return home. Karina has a pre settled status dependent on the perpetrator and is classified as non-recourse to public funds (NRPF). Although Karina was homeless and her baby at risk, she could only have access to government support when the baby was born. LAWA had to intervene to find a space in a refuge association for her last months of pregnancy and started the housing application with the local council. Until going to the maternity, Karina had no information where she would go next. When the baby was born, Karina was offered a temporary accommodation in a hotel. When she arrived, she did not feel relief. The room was filthy, it had no kitchen or windows and there were people with addiction problems in the building.

With a newborn baby and still recovering from childbirth, she cleaned the space after an intense moving day. Inadequate temporary accommodation is a reality in the UK. Many women are placed in mixed spaces without access to basic facilities like a kitchen where they can prepare meals or do the laundry. Lack of access to Internet is also a recurrent issue, along with rat infestations and mould. Once again, LAWA’s caseworker advocated for Karina to find an alternative, and she was transferred to a Bed and Breakfast style accommodation. The space Karina was allocated still presents some challenges for a recent mother; for example, she has to wash the baby bottles in the bathroom sink because the kitchen is in another level of the house. She explains that to go to the kitchen she needs to take the baby, her utensils, and take the stairs, and this was especially difficult in the first weeks after the childbirth.

As a black, Brazilian woman fleeing domestic violence Karina says that unfortunately she did not have a positive experience with the council housing team. Articulating and understanding the intersecting layers of oppression like gender, race, and migration status is fundamental to correctly assess the needs of the women, but also guarantees humanised support for women like Karina.

Gloria´s story

Gloria is a 35-year-old Colombian woman who has been living the UK since 2020. She lived with a partner in a sublet house from a mutual friend. She recently fled her home to escape this abusive relationship. She went to the police station to report a recent episode of aggression and left her house. While men are generally able to remain on the property even when the tenancy is shared, having to move out of the home is a common scenario for survivors of domestic violence. With nowhere else to go and no prior knowledge of how the social system worked, she sought help.

In the process of reaching out to public authorities, she reports being stereotyped discriminated due to her nationality and physical appearance. She says that although a police officer has been assigned to support her needs, communication has been inconsistent and intermittent. After a first cold and victimizing contact with the authorities, Glória was placed in temporary accommodation. The space where she currently lives is small, but comfortable and in a different neighbourhood where the aggressor resides. Gloria moved into this location almost two months ago but has yet to sign the lease. On this matter she claims that communication with the local housing officer has been non-existent after her entry into the property. The lack of communication from the authorities is something that causes anxiety and insecurity in women. Without a communication channel they cannot ask for support with housing issues or have no idea how long they will live in accommodation, for example. As another LAWA client said: “We are left in the dark and motherhood does not come with instability. Just the thought of having to take my baby and all my belongings and go somewhere else without warning scares me.”

The uncertainty regarding accommodation reflects on other aspects of Glória’s life. She says that the lack of stability in relation to her home affects professional decisions and her mental health. LAWA service users, such as Gloria, say that if the authorities had transparent communication, keeping them updated on their cases, it would help to establish a sense of normalcy in their lives and reduce the anxiety of being homeless again. Unfortunately, women in the process of recovery have to chase the authorities and resort to specialized services to intercede for them in this complex system.

Finally, to deal with the trauma resulting from the multiple assaults she suffered and her current life situation, Gloria turned to LAWA’s holistic approach and has been attending counselling sessions. Connecting with other women in the community has also been an important part of Gloria’s healing. Meeting women with similar experiences has helped with her emotional stability and self-esteem.

Flavia´s story

Flavia is a Brazilian, heterosexual, and mother of one. She was married for 14 years, a period of her life that she experienced financial, sexual, physical abuse, use of her immigration status to exert control and controlling behaviour. Flavia’s routine was restricted by the perpetrator, and she had no network support in the UK. She used to spend her days alone in her house taking care of their child. Flavia was not allowed to go to work and was left without access to a phone. The perpetrator had a drug and alcohol addiction, and for this reason, he barely provided food or nappies. As she recalls, most days he came back home late at night, and when he returned, he was aggressive. He shouted and hit objects, and also sexually assaulted her in different occasions, for this reason she was sleeping on the sofa. For a long time, she planned to leave her house, but she saw many obstacles: she was financially dependent, her visa was linked to the perpetrator, she was not confident with her language skills and had no idea where to start.

One day she met a woman who referred her to LAWA and Flavia decided to tell her story. She contacted the organization seeking for help to leave the house she was living with the perpetrator. LAWA’s caseworkers advised her to fill a police report and contacted immigration lawyers. Flavia went to the police station and due to the severity of the situation, they helped her to collect her belongings and leave the family house that same day. She was transferred to a temporary accommodation where she stayed 6 months and then to another self-contained flat where she currently lives.

Flavia is in a recently refurbished flat, in a neighbourhood close to public services, transport and her son’s school. She says that she is very grateful for being placed in this flat. Flavia’s case is an example of good practice, as she feels that she was listened to by the local authorities who understood the problem and acted fast to support her. Throughout the process Flavia said that the local housing and children’s service team assisted her, whether gathering donations or detecting her family needs to provide a decent accommodation. When they moved to the first temporary accommodation, this assistance was fundamental because they left the family’s house in a hurry. She says that her son was frightened with the situation, hiding behind the sofa to not leave the house. She left the home that she lived for years, just with the essentials.

Flavia says that the beginning of this journey was extremely hard, that even her did not believe when she told her story to the police. She thought nobody would believe how she could stay more than a decade in an abusive relationship. Fortunately, Flavia was supported by comprehensive and approachable staff, who took Flavia’s case seriously, helping her to start a new phase of her life. After moving to the accommodation, LAWA supported Flavia mediating the communication with the housing team and following her homeless application and child benefit. The caseworkers also contacted a solicitor to advise Flavia regarding the children’s arrangements and her immigration status.

Policy and practice updates

Coming out of our housing advocacy practice supporting black and minoritised survivors of VAWG at risk of homelessness, as well as from our continued in-depth analysis of the case files from our specialist service, and connecting with the current demands from other likeminded agencies in the VAWG and Housing sector, we propose several policy and practice recommendations to prevent homelessness amongst minoritised survivors.